An Unearthly Series - The Origins of a TV Legend

Friday, 27 September 2013 - Reported by Marcus

The twenty-first in our series of features telling the story of the creation of Doctor Who, and the people who made it happen.

The twenty-first in our series of features telling the story of the creation of Doctor Who, and the people who made it happen.After five days of rehearsing, the cast were ready to go before the electronic cameras for the recording of the first episode of Doctor Who, which took place on Friday 27th September 1963 - exactly 50 years ago today.

Later known as the pilot episode, this recording was intended to be shown as the first episode of the new series.

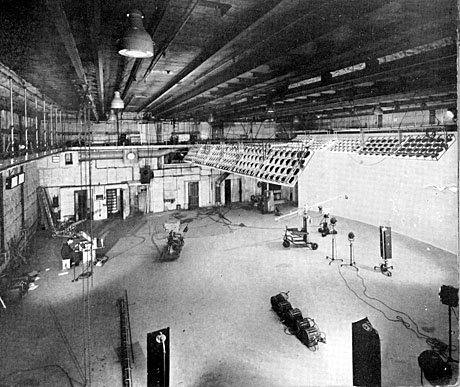

Doctor Who was to be recorded in Studio D at Lime Grove in west London. Opened in 1914 by the Gaumont Film Company, Lime Grove was a film studio converted for television. Bought by the BBC in 1950, it would be home to some of the nation's most-loved programmes for over 40 years.

Doctor Who was to be recorded in Studio D at Lime Grove in west London. Opened in 1914 by the Gaumont Film Company, Lime Grove was a film studio converted for television. Bought by the BBC in 1950, it would be home to some of the nation's most-loved programmes for over 40 years.Studio D was 5,300 sq ft, about 83ft x 64ft. Long-running series broadcast from here included What's My Line?, Sooty, Dixon of Dock Green, Blue Peter, Steptoe and Son, whose theme was composed by Ron Grainer, and Britain's first soap, The Grove Family, which took its title family from the studios, was created and written by Jon Pertwee's father and elder brother, Roland and Michael, and whose cast included Peter Bryant.

Television production in the 1960s followed a strict pattern. Overnight, the sets for Doctor Who were rigged following the plans drawn up by the designer, Peter Brachacki. Over half the studio was taken up with the interior of the Doctor's time and space ship, the TARDIS. Built by freelance contractors Shawcraft Models (Uxbridge) Ltd, the set featured a large hexagonal unit strung from the ceiling. The main console took up a large space, consisting of six instrument panels and a pulsating central column. Other sets included the school classroom and the junkyard, which featured the TARDIS prop.

Once the sets were rigged they needed to be lit. Television lighting is a skilled art which takes years of training and experience. Sam Barclay was assigned to light the episode, having just finished working on the drama Jane Eyre. As well as creating the atmosphere of the show, the lighting director also needs to make sure the characters are correctly lit by careful positioning of key lights and back lights.

Camera rehearsals took place in the afternoon. The show would be recorded as live, with just one camera break at the point the crew entered the TARDIS. This was the first time the studio crew would have a chance to run through the complete show. The senior representatives of the crew would have attended the final rehearsal the previous day and made notes to pass on to their teams. The director, Waris Hussein, supplied a camera script, with all the shots he would require listed by shot number. However, it was not until the crews started rehearsing with the cast that the pieces started to come together. In a small studio such as Lime Grove, everyone needed to be totally aware of what they should be doing, from camera operators and cable bashers, to sound boom operators, to floor managers and assistants who were responsible for making sure everyone on the studio floor was where they should be.

In the studio gallery the vision mixer, Clive Doig, would need to make sure he knew exactly which camera to cut to the recording line at each point, guided by the production assistant who would call out the camera shots. The sound supervisor, Jack Clayton, would make sure the right microphones were faded up and would mix in the special music and effects played in by the grams operator at the back of the sound booth. The technical manager would need to make sure all equipment was running correctly and in the lighting gallery all cameras were constantly adjusted to ensure they produced pictures of the same quality. Co-ordinating everything was the director. Because the show had to be recorded as live, it was essential that everything was rehearsed as much as possible to reduce the possibility of mistakes.

In the studio gallery the vision mixer, Clive Doig, would need to make sure he knew exactly which camera to cut to the recording line at each point, guided by the production assistant who would call out the camera shots. The sound supervisor, Jack Clayton, would make sure the right microphones were faded up and would mix in the special music and effects played in by the grams operator at the back of the sound booth. The technical manager would need to make sure all equipment was running correctly and in the lighting gallery all cameras were constantly adjusted to ensure they produced pictures of the same quality. Co-ordinating everything was the director. Because the show had to be recorded as live, it was essential that everything was rehearsed as much as possible to reduce the possibility of mistakes. The cast were made up by the make-up department headed by Elizabeth Blattner, and William Hartnell was fitted with his wig. Costumes were supervised by Maureen Heneghan.

After a supper break the recording of that first episode began, with the first person to step in front of a camera being Fred Rawlings playing a policeman who, while on night beat amid mist and as a clock bell is heard to strike three times, shines his torch over the gates of a scrap merchant called I. M. Foreman, at 76 Totter's Lane . . .

It is difficult to imagine the pressures in the studio as the team brought that first episode to life. For such an innovative drama, though, problems were inevitable. The recording for that pilot episode is available to watch in full on The Beginning DVD box set. One of the biggest problems was with the doors on the interior of the TARDIS set. They refused to close and can be seen flapping open behind the main characters. Because of the problem, Hussein made the decision to retake the final half of the show. The section from the break where the crew entered the TARDIS to the end of the episode was performed again, this time to the satisfaction of the director and producer.

Verity Lambert

It was terribly ambitious, it was hard. It was our first day in the studio, we had these awful cameras, we had Sydney [Newman - Head of Drama] coming in saying he hated the titles and the title music. Everyone was under tremendous pressure.

It was terribly ambitious, it was hard. It was our first day in the studio, we had these awful cameras, we had Sydney [Newman - Head of Drama] coming in saying he hated the titles and the title music. Everyone was under tremendous pressure.

Waris Hussein

All my wonderful visual shots that I'd designed on paper were now going to have to be manifested by these monstrous cameras that were so heavy that the cameraman couldn't move.

It had been a long process but, to the relief of Hussein and Lambert, the first episode was now in the can. It would be shown to the bosses the following week. The cost of the recording session was later estimated to have been £2,143, 3 shillings, and 4 pence (£2,143.17). All my wonderful visual shots that I'd designed on paper were now going to have to be manifested by these monstrous cameras that were so heavy that the cameraman couldn't move.

SOURCES: Doctor Who: Origins, The Beginning, DVD Box Set, BBC Worldwide; An incomplete history of London's television studios; The Handbook: The First Doctor – The William Hartnell Years: 1963-1966, David J Howe, Mark Stammers, Stephen James Walker (Doctor Who Books, 1994)

In the days before video editing, complicated sequences, or items that required a lot of setting up, would always be recorded on to film. Film was a much more flexible medium than video tape, primarily because it could be easily edited.

In the days before video editing, complicated sequences, or items that required a lot of setting up, would always be recorded on to film. Film was a much more flexible medium than video tape, primarily because it could be easily edited.

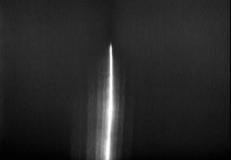

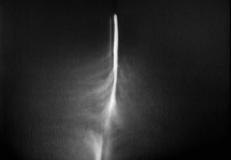

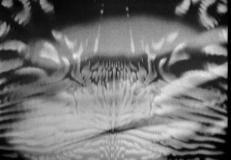

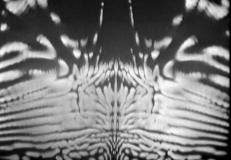

An experimental session, testing new electronic effects for the series, had originally been planned for Friday 19th July, and it finally took place on Friday 13th September 1963, exactly 50 years ago today.

An experimental session, testing new electronic effects for the series, had originally been planned for Friday 19th July, and it finally took place on Friday 13th September 1963, exactly 50 years ago today.

Norman Taylor

Norman Taylor

Bernard Lodge

Bernard Lodge

Grainer was an Australian composer who had been living in London for the past ten years. After working as a pianist in a nightclub, he had achieved some success as a composer, creating the scores for a number of TV series and a couple of features films. In 1961 he had won an Ivor Novello Award for the theme to Maigret, the series based on the books by Georges Simenon. Grainer had already worked with the Radiophone Workshop when creating his score for Giants of Steam, a documentary about railways.

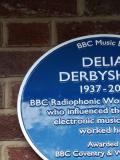

Grainer was an Australian composer who had been living in London for the past ten years. After working as a pianist in a nightclub, he had achieved some success as a composer, creating the scores for a number of TV series and a couple of features films. In 1961 he had won an Ivor Novello Award for the theme to Maigret, the series based on the books by Georges Simenon. Grainer had already worked with the Radiophone Workshop when creating his score for Giants of Steam, a documentary about railways. Assigned to create the music would be one of the Radiophonic Workshop's staff,

Assigned to create the music would be one of the Radiophonic Workshop's staff,  Another important element of the show would be the special sounds. In charge for the first episode would be

Another important element of the show would be the special sounds. In charge for the first episode would be

July 1963 was mostly cool and changeable as production at Television Centre in west London continued on the new television drama, which by now had a name, Doctor Who. Producing a television drama is a complicated thing, with so many departments needing to work together and so many people all needing to make sure their part of the puzzle would fit into the whole picture. One of the most important parts of the whole is design. Design in Television is vital, especially in science fiction drama where new worlds and future landscapes need to be created. The requirements for the new programme were enormous and producer

July 1963 was mostly cool and changeable as production at Television Centre in west London continued on the new television drama, which by now had a name, Doctor Who. Producing a television drama is a complicated thing, with so many departments needing to work together and so many people all needing to make sure their part of the puzzle would fit into the whole picture. One of the most important parts of the whole is design. Design in Television is vital, especially in science fiction drama where new worlds and future landscapes need to be created. The requirements for the new programme were enormous and producer  Music is another vital element in a television drama and Lambert was determined to try something different on this series. On Friday 12th July she made enquiries about commissioning the French electronic music composers Jacques Lasry and Francois Bascher to provide the title music for the series. Their group, Les Structures, were known for creating music using such techniques as glass rods mounted in steel.

Music is another vital element in a television drama and Lambert was determined to try something different on this series. On Friday 12th July she made enquiries about commissioning the French electronic music composers Jacques Lasry and Francois Bascher to provide the title music for the series. Their group, Les Structures, were known for creating music using such techniques as glass rods mounted in steel.

Tucker was friends with an actor called

Tucker was friends with an actor called  In 1961, Lambert had taken a break from ABC to work for a year as the personal assistant to noted American television producer David Susskind in New York. She returned to the UK in 1962, determined to become either a producer or a director, but no opportunities for promotion were forthcoming, and she remained as a production assistant at ABC.

In 1961, Lambert had taken a break from ABC to work for a year as the personal assistant to noted American television producer David Susskind in New York. She returned to the UK in 1962, determined to become either a producer or a director, but no opportunities for promotion were forthcoming, and she remained as a production assistant at ABC.